One year ago, I spent a large amount of concentrated time at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in Westwood. Up until that point, I had been fortunate enough to spend minimal time in a hospital, for myself or my loved ones— never staying more than a few days or visiting sporadically. But, in April 2024, my partner José had a sudden and massive heart attack, and was taken to the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in an ambulance, where he stayed for three weeks.

As probably anyone who works in one or who regularly visits can tell you, hospitals are very strange places. They are buildings that serve many different functions— a workplace, a short-term or long-term living place, transitory places, places of commerce and innovation, of grief, fear, and joy. Their designs have a lot to balance. For visitors, I think their main job is just not to make a bad situation worse.

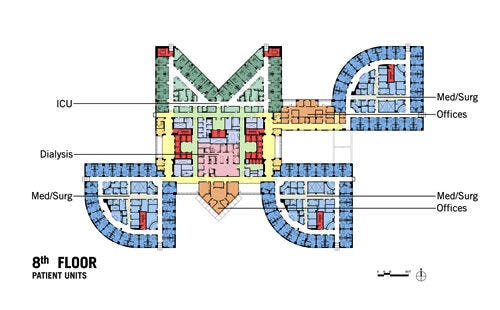

When I arrived in a panic at the Ronald Reagan Medical Center last April, I was left completely disoriented. The building is situated in the larger UCLA Medical Plaza, a collection of at least eight structures located on the south side of UCLA’s campus. Designed by Didi Pei, in collaboration with his extremely famous architect father I.M. Pei, the building opened in 2008 to replace a nearby hospital that had been damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake. It was designed to withstand an 8.0 earthquake, and Pei Architects report that they aimed to allow in as much natural light as possible. I believe that is the reason for the curious configuration of the upper floors, including the cardiac unit I spent my time in. At some point during José’s stay, someone told me the layout was in the shape of an “M” for I.M. Pei— I have absolutely no recollection of who reported this (perhaps a nurse?), but upon reflection it seems completely preposterous.

My time at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center was spent mostly in the waiting rooms of the cardiac unit, places at the time I detested, but now one year later, especially having been in a few other hospitals for follow-up appointments since, I can say were actually well-executed. While too small and featuring standard-issue hospital waiting room chairs, the rooms had natural light and could be closed off for privacy. There were sort-of balconies attached, though they were inaccessible and only home to some dying flower beds.

The sun streamed through the hallway windows at 5pm every day, and I would silently thank I.M. Pei himself for allowing natural light to hit my face for a few minutes instead of the florescent hospital lighting. This also coincided with the natural rhythms of the hospital, something that an extended visit allows you to really tune into. Day doctors go home, a new shift starts, things quiet down, and you can spend more time with your loved one in the unit.

Every day, I could watch the sunset over the Santa Monica Mountains through these windows. As the days and weeks continued, they became the frame from which I viewed the world, besides the screen of my phone.

Inside the cardiac ICU, design was keeping José alive in a very different way. He was put on an ECMO, also known as a extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation machine. It was an approximately R2D2-sized contraption that pumped and oxygenated his blood, so his body could rest and recover from having a heart attack. A person can live for a long time on ECMO, and sit and walk around, though always confined to the ICU.

One year later, José is mostly healthy, though physical and mental scars remain. We just celebrated his “lifeaversary”— a term brought into my life by one of my beloved friends from college— and reflected on the past year.

When I think about the time I spent at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, more than the florescent lighting, the uncomfortable chairs, or the constant din of automatic doors opening and closing, I remember how other people made me feel. Being in a hospital involves talking to a lot of people every day— and some of these make an impression. A nurse with a fascinating backstory, a doctor willing to make small talk about my name, ECMO technicians with jokes stick out in my memory. But, even more, I remember the way my friends and José’s friends showed up, in ways and amounts I never expected.

Being in a hospital requires you to accept care. You’re either the patient, required to receive the medical care you need, or, someone affected, with priorities suddenly shifted far, far away from feeding or caring at all for yourself. The entire cladding of the Medical Center is a monument to care— the travertine was donated at below market rate by an Italian quarry magnate as a thanks for the cancer treatment he received there1. My friends and family brought food, gifts, cards, flowers (not allowed in the cardiac ICU), and hugs. I had previously experienced something similar when I was injured in a car accident a few years ago, but this time, as I was not the one injured, it registered differently. Not required, but simply kind and caring.

I had long read about “community care” as a radical act, but as I found myself the subject of it, I experienced it in practice through the generosity and kindness of others. However, during the month, I also watched it play out on my phone. While my days were spent in the Pei designed-hermetically sealed tower of the cardiac unit, down below, UCLA was the center of college Palestine protests in Los Angeles. Their “liberated zone” was large and well-established, before being attacked by counter-protestors and eventually required to disassemble by the LAPD. One of my friends came from the east side of Los Angeles to drop off a card for me and bring supplies by the UCLA encampment, an act that brought tears to my eyes when I considered the levels of thoughtfulness and significance.

Modern daily life allows for so few displays of community care if you do not specifically seek them out. Capitalism seeks to destroy every possible permutation of it, championing individualism and charity2. I’m not sure if what I experienced counts as full-on solidarity in the political sense, but I know I felt “purpose, interest, and sympathy” (part of a definition of solidarity) from my friends. Sitting in the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center a year ago, I frequently contemplated how Reagan was once a union president, yet dismantled labor unions while president of the United States3. I thought about how José only had health insurance thanks to his workplace’s union, and how the United Auto Workers union local 4811, representing 48,000 academic employees at UC campuses, went on strike that May in support of pro-Palestine student protests4.

I hope that as life offers me more opportunities to show up for people and practice solidarity, I will take them. All we have is each other. I will always be thankful for what others offered me during this challenging last year, whether it was the natural light provided by an architect, or the love provided by my friends and family.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you somewhere next week.

You can read more about solidarity versus charity here in Mutual Aid by Dean Spade.